The beginning of Australian embarked naval aviation is usually associated with the flying-off experiments of Sopwith Pups from HMA Ships Sydney and Australia in December 1917. But six months earlier on 6 May 1917 HMAS Brisbane achieved the distinction of being the first Australian warship to embark and operate a powered aircraft at sea. The aircraft was a Blackburn Baby seaplane loaned to Brisbane by the Royal Navy Seaplane Tender HMS Raven II. Brisbane flew the single-seater in May 1917 during the search for the German raider SMS Wolf in the Indian Ocean. It is also likely that Brisbane conducted a second embarkation of an aircraft late May and early June when the ship searched the Bay of Bengal, but the records to confirm this have not been located.

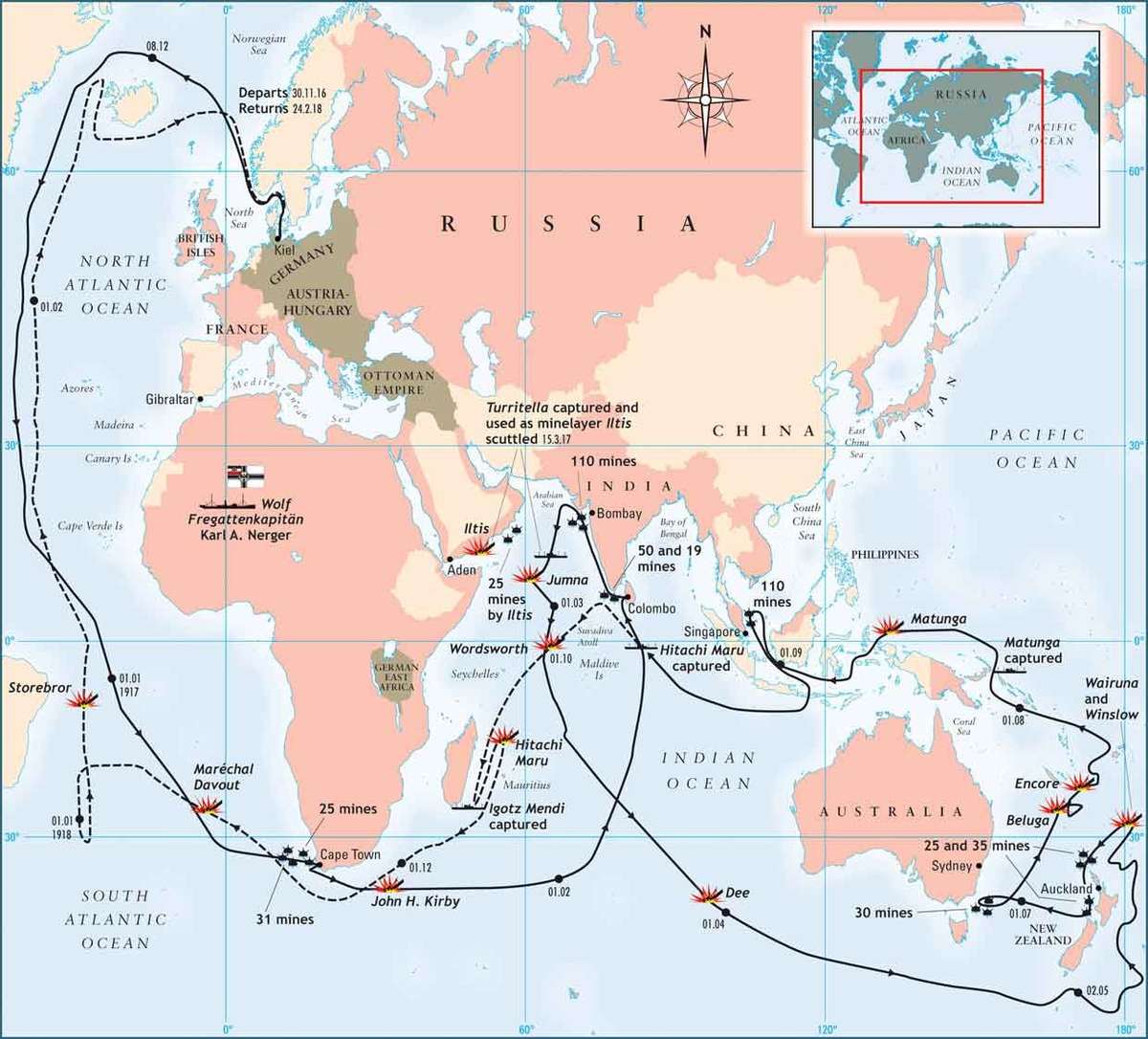

At the request of the British Admiralty, Brisbane left Port Jackson on her first deployment in December 1916, bound for the Mediterranean. After two months at Malta the cruiser was despatched to the Indian Ocean to search for an unknown enemy sea raider later determined to be the German Wolf which with her own seaplane, a two-seat Friedrichshafen FF33e named Wolfchen (Wolf Cub or Little Wolf), had departed her home port of Kiel on 30 November 1916 with the mission to raid shipping and lay minefields in the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans.

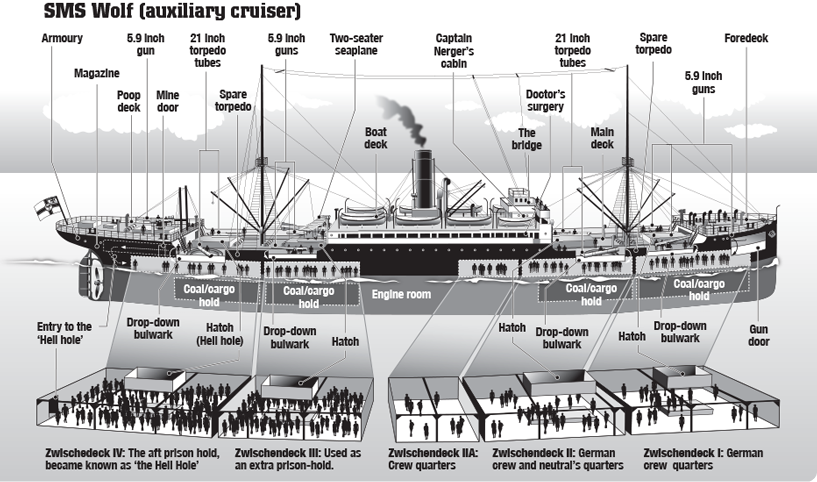

Wolf, although by appearance a merchantman, was heavily armed with 6 x 5.9 inch, 3 x 2 inch and a number of smaller calibre guns and 4 torpedo tubes. She also carried in excess of 450 mines. By end of May 1917 Wolf had sunk some 4 ships by direct action and her mines had accounted for another 5. When Wolf eventually berthed back at Kiel on 24 February 1918 she had sunk 14 ships directly and 13 with her mines. She also carried more than 450 prisoners captured from her victims.

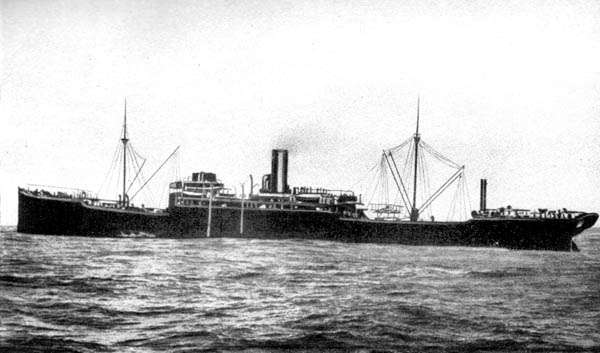

Above: The Wolf looked innocuous enough, but it packed a potent punch with 6×5.9inch guns, four torpedo tubes and over 450 mines. Her principal defence was deception: the appearance of a merchant vessel and, from time to time a change to her profile by raking her funnel or erecting or lowering masts. Her weaponry was behind hidden drop down bulwarks.

The drawing below by Paul Leigh gives a good idea of the layout of the ship, including stowage for prisoners captured from enemy vessels (click to expand).

Below: SMS Wolf set out from Keil at the end of November 1916 with a crew of 348 men. She returned 451 days later, making it the longest voyage of any warship during WW1. She carried 467 prisoners of war as well as a considerable haul of rubber, copper, brass and other essential materials taken from her prizes. Fregattenkapitan (Commander) Karl Nerger, the commanding officer, received the highest German decoration, the Pour le Mérite. (Click on image to enlarge).

The Wolf Cub

SMS Wolf’s embarked seaplane was a Friedrichshafen FF33e of which 180 were constructed during WW1. The aircraft was largely responsible for the location of its parent ship’s victims and was named Wolfchen (or Wolf cub). It is recorded as having captured two vessels in its own right. At 54ft 6in (16.6M) the FF 333e had over twice the wing span of the Sopwith Baby and was 10ft 6in (3.2m) longer. The loaded weight of Wolfchen was 1550kg and twice that of the Baby 779kg. The physical size of the aircraft would have made the FF33e much more unwieldy than the Baby to lower and raise over the ship’s size and the aircraft also presented a greater stowage challenge. The Wolf’s FF 33e had its wings removed after every flight partially because of their size and also to protect them from blast damage by gun fire.The FF 33e was powered by a Benz inline liquid-cooled engine of 150hp. The Baby had a 110hp Clerget engine. The FF33e is unlikely to have been a startling performer in terms of manoeuvrability or rate of climb but its endurance was 5 to 6 hours and more than twice that claimed for the Baby was a positive attribute for its reconnaissance role.

Probably the greatest advantages enjoyed by the FF 33e were that it had a crew of two and was equipped with a wireless. The second crew member would have been of enormous advantage releasing from and hooking the aircraft onto the whip of the ship’s crane but also conducting navigation and communication both with Wolf by radio, and intended victims. The standard method of communication with victims was to drop a note written in English onto the target ship demanding surrender and directing a heading toward Wolf be immediately followed. Resistance caused the aircraft to drop a bomb just ahead of the ship. This procedure appears to have been successful in capturing all of the ships apprehended by Wolfchen. The Sopwith Baby is not known to have ever been required to perform such a role and even though it was armed with a Lewis Gun and bomb racks it is unlikely the aircraft would have found it practical to do so. But the Baby was a general purpose and for its time a handy ‘maid of all work” aircraft and not optimised for any particular role but used for most. 386 Babies were built.

The FF 33e Wolfchen was reportedly airborne over Wolf when the ship entered Kiel at the end of its 15 month deployment. Considering the ship had not enjoyed any support from ashore during that time, the evident serviceability of the FF 33e is a considerable testament to the aircraft’s design and to the competence of the embarked flight.

By March 1917 Wolf was beginning to generate a great deal of consternation in the governments of the Allies. The Official History of the Great War: Naval Operations Vol. IV by Henry Newbolt states that there was no definite intelligence on the Wolf until early March. And he records that in March of 1917 there were approximately 24 British, Australian, French and Japanese naval vessels deployed throughout the Indian Ocean on patrol and escort duties in response to the threat of the raider.

By the end of April the light cruisers HMS Gloucester and HMAS Brisbane had arrived at Colombo from the Adriatic and Malta respectively, and the seaplane Tender HMS Raven with the French cruiser Pothuau had been directed from the Red Sea to Colombo. The significant Japanese contribution has largely been forgotten. Newbolt acknowledged in the official history that the Imperial Japanese Navy did more than was asked of them and had at one point provided up to ten cruisers and destroyers in the Indian Ocean and Western Pacific in response to the threat of the German raider.

Brisbane’s embarkation of an aircraft was but one consequence of Wolf’s foray into the southern oceans.

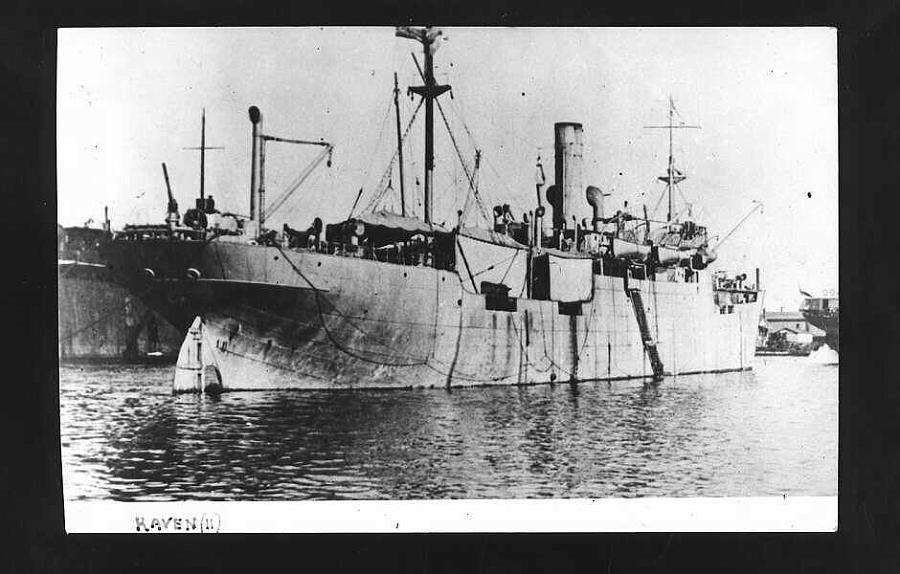

Above: HMS Raven II was a seaplane carrier used by the Royal Navy during WW1. Ironically, she was converted from the German freighter Rabenfels, which had been captured in Port Said in August 1914. Aircraft were stowed on the aft hatch covers and handled with her cargo booms. After the war she was sold to a succession of operators until she was sunk in WW2 whilst under Japanese ownership.

Below: Blackburn Baby N1014 being hoisted aboard HMAS Brisbane. It is not known who the figure in the cockpit is, but it may well have been Flight Commander Clemson. (Image: Australian War Memorial).

Raven, which had Short 184 seaplanes and one Blackburn Baby seaplane embarked, was under the control of the outstanding and indomitable FAA pioneer Commander RN later Air Commodore Charles Rumney Samson, CMG, DSO & Bar, AFC, RAF. Commander Samson and Flight Commander Clemson who was a pilot aboard Raven had worked and flown together before, in the Dardanelles.

Raven arrived at Colombo in early April 1917 in company with the French cruiser Pothuau after searching the Laccadive Islands during their transit from the Red Sea.

While the ships were coaling, arrangements were made for Raven and Potuau to search the Maldive and Chagos Islands with the Short seaplanes. Additionally the Baby was to be transferred to Brisbane with the intention that the Australian ship should search further reaches of the Indian Ocean. This particular aircraft, which carried the Royal Naval Air Service serial number N1014 (referred to as “Sopwith 2014” in Raven’s Log), was one of the first batch licence-built by Blackburn. After the aircraft’s embarkation with four maintainers on 6 May 1917 it was stowed aft on the upper deck of Brisbane on a platform designed by the ship’s CO, Captain Claude Cumberledge RN. For flight operations the Baby was craned overboard from this stowage and would take off from the sea and, after landing, would then be hoisted inboard.

Although Brisbane’s search did not find the Wolf because the raider by this time was well to the south of Australia travelling eastward, the embarked Baby operated successfully from its new parent ship during the embarkation 6 to 15 May 1917, reportedly making two flights daily each of an hour’s duration in the early morning and late afternoon. The dates and duration of the embarkation are assumed from the entries in Raven’s log recording when the aircraft, pilot and maintainers were transferred to and from Brisbane. The pilot was Flight Commander A.W. Clemson RNAS who impressed CO Brisbane with his most competent conduct of his duties.

In late May 1917 Raven was recalled to the Red Sea to participate in the ongoing operational tasking in the Middle East.

According to Raven’s log Brisbane sailed with her. Before sailing Sopwith 2014 had on 17 May 1917 been disembarked from Raven with eight maintainers to the depot at Colombo. The Baby continued to conduct searches to seaward from ashore. On 22 May 1917 Raven also recorded Brisbane’s departure to Bombay. The ship is likely to have again embarked the Baby with CMDR Clemson as it passed (then) Ceylon on passage to the Bay of Bengal.

On 1 or 2 June June 1917 the Admiralty advised that escorts were no longer required in the Indian Ocean. Brisbane returned to Colombo, disembarking its aircraft upon arrival and later sailing from the depot for Australian water on 14 June 1917.

HMAS Brisbane was not the first allied warship to embark and operate an aircraft. Many RN cruisers were appropriately equipped to conduct such operations and had done so. The cruisers Doris and Minerva, amongst others, had operated aircraft at Gallipoli in 1915. And there had been many similar embarkations since then. By May 1917 the Royal Navy had approximately eight to ten seaplane tenders in service. It is difficult to be sure of the precise number because some of these ships were Royal Fleet Auxiliaries (RFA) and therefore do not always appear in the RN’s records of activity. The RN could field a substantial number of aircraft from these ships and cruisers at sea.

The seaplane’s mode of operation was cumbersome, however, and limited by ship’s motion in any significant sea. Additionally the weight and aerodynamic drag of floats imposed a considerable penalty upon aircraft performance, and ships’ captains did not enjoy the vulnerability of being stopped dead in the water while the lowering and hoisting an aircraft.

So the next stage of the development of naval aviation was rapidly progressed. This involved the fitment of launch platforms mounted upon gun turrets and the introduction of aircraft with substantially better performance than the Baby, particularly the Sopwith Pup and Camel. Australian ships played a leading role in this development. Although launching was much easier from these platforms, the recovery of these “once only” aircraft (introduced primarily to counter the threat from Zeppelins) remained an unsolved problem – unless the parent ship was within diversion range of land. The development of the conventional flush-decked aircraft carrier was the answer, and was also well underway by late 1917.

Above. A Sopwith 1½ strutter No.5644 launches from HMAS Australia in March 1918, using an extendible 30ft platform over one two of its gun turrets. The ship could carry two aircraft: typically a Sopwith Pup or Camel, and a Sopwith 1½ Strutter as a reconnaissance aircraft. Although the platform allowed the ship to launch an aircraft without stopping, the problem of recovery remained, with the aircraft either having to divert ashore or ditch alongside the ship.

Above. Another view of a Sopwith Camel aboard HMAS Sydney I. Although the platform offered greater flexibility than having seaplanes, recovery of the aircraft remained a significant problem. This led to the concept of the flush-deck carrier, which could launch and recover aircraft. HMS Argus (right), painted in dazzle camouflage, was the first such vessel in the world. She was converted from an ocean liner and served in the RN from 1918 to 1944, during which time she did much to assist in the optimum design for future generation aircraft carriers. The RAN was not to operate a vessel with a full flight deck until 1948.

The milestone achieved in 1917 by Brisbane does not to appear to have resonated with naval authorities. Perhaps because the embarkation of an aircraft was by then a well proven procedure within the RN it was not considered out of the ordinary. Captain Cumberledge, who is remembered as an advocate of embarked aviation, is brief in his coverage of the embarkation as indicated by available correspondence generously provided by CMDR David Stevens, the author of In All Respect Ready: Australia’s Navy in World War One. CO Brisbane appears to have provided insufficient quantitative or qualitative data to enable a useful assessment of how to safely conduct a future embarkation and to determine the attending logistic implications. Perhaps a significant part of his follow-up reporting has been lost.

After WW1 the RAN had considerable complexity to implement budget and substantial reductions of personnel. It is beyond the scope of this article to explore the politics and inter-service competition which contributed to naval aviation in the immediate post war years not rising to the top of future capability requirements. For a decade after WW1 very little aviation occurred in the fleet apart from the brief, desultory and unsuccessful trial of Avro 504k aircraft on the cruisers Australia and Melbourne in 1920 and the brief embarkation of a Fairey IIID in HMAS Geranium for survey work during 1924. Though all was not lost. After 10 years of difficult negotiations and accommodations to provide for the more usual naval capabilities the RAN’s first aircraft carrier HMAS Albatross, a locally built Seaplane Tender was commissioned on 23 January 1929 and manned largely by former members of the ship’s company of HMAS Brisbane which had paid off the day before. On 25 February 1929 six Seagull III’s of RAAF 101 (Fleet Cooperation Flight), were embarked in the new ship. The Flight later became RAAF 5 Squadron and finally RAAF 9 Squadron. The RAAF presence resulted from a 1928 cabinet decision under which RAAF provided the aircraft, their maintainers and pilots while Navy provided observers and telegraphists. Naval officers were permitted to train and serve with the RAAF as pilots.

On 20 July 1922 the purchase of Six Supermarine Seagull III had been proposed for the RAAF by the Air Council. The procurement was to replace the Fairey IIID for the marine surveying task. The order was confirmed by the Minister for Defence 27 April 1925. The RAN’s Seaplane Tender HMAS Albatross was ordered in mid-1926, apparently as a political strategy to settle the concerns of the Australian ship-building industry regarding Australia’s order the previous year of two British-built cruisers and two submarines. The Chief of Air Staff of the time reportedly learnt of the decision from the newspapers.

HMAS Albatross was the RAN’s first aircraft carrier, but was obsolete by the time she entered service. The full story of her time in the RAN can be found here.

The performance of the Seagull III was not good, as can be seen from a report of a Survey flight in PNG.

‘Except on three or four occasions the machines had not much difficulty in getting off the water. There was however a marked lack of performance in the air with full load, and the performance became progressively worse for the first month of the trip. It was then difficult to get them to stay at 400 feet in still air. On bumpy days it was not possible to get higher than three or four hundred feet for the first couple of hours of each flight. Judged by these performances the machines are not suited for service requirements of the nature of photographic mapping.’

Edge of Centre: The eventful life of Group Captain Gerald Packer RAAF Museum Point Cook by C.D. Coulthart-Clark.

As one consequence of the Albatross acquisition, RAAF’s procurement of six Seagulls was increased to nine aircraft, to provide for the training of personnel for embarked operations. Interestingly, in 1925 (i.e the year before) the Royal Navy had paid off the Seagull III after a service life of only two years to replace it with the Fairey IIID – exactly the reverse of what the RAAF did. At the time of the Australian order of an additional three Seagull III aircraft CAS anticipated a more appropriate type of aircraft would be procured when the Albatross entered service.

Another type of aircraft never materialised, although the need appears to have been regularly discussed by Defence. In March 1928 the purchase of 16 Fairey IIIFs for the new cruisers Canberra, Australia and Albatross “pending further development of amphibious aircraft” was authorised by the Minister for Defence. The order never went though, reportedly because Navy wished to procure the yet un-trialled Fairey IIIF variant with an air-cooled (rather than liquid-cooled) engine.

The replacement of the Seagull III was complicated by the locally produced, developmental and ultimately unsuccessful Wackett Widgeon and also by the RAAF’s specification in the mid 1920’s of an amphibian aircraft that eventually became the most successful Seagull Mk V and Walrus. An off-the-shelf solution was apparently not favoured. The first Seagull V was delivered to HMAS Australia 9 September 1935 at Spithead, the second to HMAS Sydney the following month. The remaining 22 of the original order were delivered to Australia by sea.

As the RAN and RAAF prevaricated over the potential aviation capability of Albatross, the RN meantime was placing considerable emphasis on developing and introducing effective cruiser compatible aircraft and catapult systems, together with attendant doctrine for reconnaissance, spotter, torpedo and bomber roles. The RN had paid off most of the Seaplane Tenders immediately after WW1. During the period 1927 to about 1935 the RN had introduced and then replaced about 6 different aircraft types into embarked service with catapults and hangars of increasing capacity. Albatross could be viewed as an obsolescent capability. The Supermarine Seagull III certainly was obsolescent by 1929. However the RAN was, albeit at a leisurely pace, proceeding toward an embarked aviation capability with the new cruisers and the retro-fitment of that capability to older ships.

Albatross was not fitted with a catapult until 1936 (to perform trials with the Seagull V) by which time she had been in reserve for three years. Until that time the procedure for operating embarked aircraft was substantially the same as that followed by Raven and Brisbane over 12 years earlier.

There were other deficiencies, too: for example, Albatross with a maximum speed of 22 knots was noted as being too slow to keep up with the cruisers. These ships were capable of 34 knots, were increasingly dependent upon aircraft and were considered to be the “eyes of the fleet” . However in favourable conditions and when high speed was not required, Albatross during her short period of service did demonstrate that with her aircraft she was able to effectively work with the fleet and perform reconnaissance, hydrographic survey work, gunnery and torpedo spotting. As the RN had proven, however, but these tasks could be performed by cruiser borne aircraft at much lower cost. . The cruisers Australia and Canberra embarked Seagull III until 1936 when the aircraft reached Life of Type.

Albatross was paid off into reserve in April 1933, but was recommissioned in April 1938 and transferred to the RN in part-payment for HMAS Hobart. By then catapult equipped RAN cruisers were fitted with the amphibious Seagull Mark V and Walrus aircraft. Operation of these aircraft aboard RAN cruisers and Armed Merchant Cruisers (HMA Ships Manoora and Westralia) continued until the latter years of WW2, when improved radar and increasing dominance of allied naval power rendered them obsolescent. Their war service remains little remembered.

At the end of WW2 naval aviation, as limited as it was, once again appeared threatened but after a huge amount of hard work in Navy Office and elsewhere in August of 1947 the RAN’s own Fleet Air Arm was formed and our conventional carrier era began. And that is another story.

It all began a century ago when HMAS Brisbane was the first Australian ship to embark and operate an aircraft at sea. That is worth remembering on 6 May 1917.

References.

- Official History of the Great War: Naval Operations Vol. IV by H. Newbolt.

- In All Respect Ready: Australia’s Navy in World War One by CMDR D. Stevens RAN.

- War in the Air Vol. VI by H.A. Jones.

- The Sky their Battlefield by T. Henshaw.

- First of the Line by Group Captain K. Isaacs AFC, ARAeS, RAAF (Retd).

- Australian Naval Aviation Part 1 by Group Captain K. Isaacs AFC, ARAeS, RAAF (Retd).

- The Wolf by Richard Guilliatt and Peter Hohnen.

- The Acquisition of HMA Ships Albatross, Sydney and Melbourne by A. Wright.

- Sopwith Baby (Windsock Data File) by J.M. Bruce.

- Flying Stations by Australian Naval Aviation Museum: A Story of Australian Naval Aviation.

- World Wide Web Sites Various.

- British Naval Aircraft since 1912 by O. Thetford.

- Military Aircraft of Australia by S. Wilson.

- Seagulls, Cruisers and Catapults. Australian Naval Aviation 1913-1944 by R. Jones.

- Catapult Aircraft: Seaplanes that flew from ships without Flight Decks by L. Marriot.

- Flypast: A Record of Aviation in Australia by N. Parnell and t. Boughton.

- Fights and Flights by ACDRE C.R. Samson CMG, DSO, AFC, RAF.